Episode 25

Mental health and the workplace

Susanna Harkonen, Nina Hedegaard Nielsen

Episode 81

Global employment in 2026: A fragile stability

Marva Corley-Coulibaly, Stefan Kühn

Episode 80

Social Summit for Development: What it means for the world of work

Juan Somavia, Sabina Alkire, Manuela Tomei

Episode 79

Can the Doha Summit revive global social justice?

Claire Courteille-Mulder

Episode 78

Social development: progress made and promises to be fulfilled

Sabina Alkire, Manuela Tomei

Episode 77

How advancing social justice can shape the future of work

Caroline Fredrickson

Episode 76

Why paternity leave matters: lessons from Oman and beyond

Laura Addati, Khadija Al Mawali

All episodes

Mental health and the workplace

10 October 2022Research by the ILO and the WHO has found that billions of working days – and so billions of dollars – are lost every year because of work-related mental health issues, and they have called for concrete measures to address this growing problem.

What are the psychosocial risks associated with modern workplaces, and can we make mentally healthy workplaces the new norm?

Susanna Harkonen, member of the WHO’s Pan-European working group on workplace mental health, and Nina Hedegaard Nielsen, Chief policy advisor on occupational health and safety at The Danish Confederation of Professional Associations, join us to explore how we can improve psychosocial health and safety at work.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to this edition of the ILO's Future of Work podcast.

I'm Sophy Fisher.

Today, we are going to look at mental health

and psychosocial risks at work.

Every year on the 10th of October, we mark World Mental Health Day.

This year, the World Health Organization and the ILO has sounded an alarm,

calling for concrete action to address mental health issues.

Their data has estimated that 12 billion working days are lost

every year through depression or anxiety alone.

This is costing the global economy almost a trillion dollars.

What's more, it seems that the COVID-19 crisis

and the lockdowns and disruption that came with it have made

the mental health situation more acute.

What can we do to improve mental health in the workplace?

Joining me to discuss this are Nina Hedegaard Nielsen

and Susanna Harkonen.

Nina Nielsen is joining us from Copenhagen and Denmark,

where she is chief policy adviser on occupational health and safety

at the Danish Confederation of Professional Associations.

She is a qualified occupational psychologist

and international consultant on occupational health and safety,

specializing in psychosocial risks, violence and harassment,

workplace representation, and working time.

For more than a decade, she's worked with the Danish trade unions

and the Danish Labor Inspectorate looking at psychosocial risks in workplaces.

Susanna Harkonen is with me in our Geneva studio.

She is founder of Inner Work.

That's an umbrella grouping of professionals and companies working

on all aspects of mental health.

She is a member of the WHO's Pan-European Working Group

on Workplace Mental Health.

She has master's degrees in counseling psychology

and business administration

and advises organizations and leaders on psychosocial health and safety at work.

Welcome to you both, Susanna and Nina.

Thank you very much for joining us.

Let me start by asking you, why does this issue matter?

Susanna, let me start with you.

-The numbers around mental health are quite staggering.

Depending on the statistic, depending on the source,

it can be anything from 30% to even 90% of people who have been impacted

by mental health challenges.

Now, when we talk about mental health,

we are not talking about mental illness.

We all have mental health, just as we have physical health,

and then there's mental health and mental ill health.

It's important to make a difference.

At the moment, many people are unwell,

none of today's stressors are normal, and yet there's more than 90% of the staff

who wants to work for a mentally healthy organization.

This is in particular the case with the younger generation.

We can no longer ignore this.

-Nina, I have seen statistics that say

that more than half of all the working days lost

in the European Union

can be linked to work-related stress

and that depression alone is estimated to have cost the EU €600 billion.

Do you think that's accurate, or is that an overestimation?

-Well, I think it's accurate,

or maybe an underestimation, actually, because there were so many people

that are infected by stress and mental illness.

Often,

people, when they call in sick, they wouldn't say

that they're sick because of stress.

They may say they have the flu, or they may have a sore throat,

say nothing

because it's still a stigma.

I don't know anybody who doesn't know anybody in the family

or in the close relation that has been ill with stress.

It is a huge problem.

I think it's an understatement, not an overstatement,

actually.

-Susanna, you work a lot with private clients

and with organizations on workplace mental health issues.

Can you give us some examples of some of the ways this

has manifested itself?

-With individuals.

Individuals, often it's related to working hours.

It's probably the biggest one.

Too long,

there's no limits.

Holidays, you still have to clock in

or you're not officially expected to, but in actual practice,

or company culture, organizational culture support it.

That's probably the biggest one of the workplace as well.

Then one which I'm seeing increasingly is that individuals are getting frustrated

because the companies are saying one thing and doing another.

The public discourse says,"

Oh, we care for our employees.

We care for their mental health,"

but nothing is being done in actual practice.

That makes people very angry, very upset.

Actually, there's recent research about this resentment and anger are

the prevailing emotions among employees in the workplace.

-Do you think that COVID-19 made this worse,

or do you think the levels that we're seeing now,

were they always there and we just didn't notice

until after people became more aware of these issues because of COVID?

-I think that the issues were already there before COVID,

and COVID just made them visible.

It may have exaggerated those in a couple of areas.

By and large, they were definitely there before that.

I'm glad that we can now speak about them because before COVID,

even mentioning stress to organizations was a little bit

of a taboo.

-Tell us a bit more about some of the things

that cause psychosocial problems, psychosocial risks at work.

-When the reason WHO and ILO report the recommendations on mental health

at work, they identify 10 risks.

For example, we already mentioned working hours

and work pace, work schedules,

control of one's work, environment and equipment,

interpersonal relationships that work is a huge one at the moment

because when people are unwell, they have a hard time relating well,

and then emotions may come to the surface that are not very constructive.

Their role in organization is one of them career development

is that's being stalled,

and then homework interface is a bigger and bigger issue at the moment

because of COVID.

How do we navigate that space?

For some people, it's a positive thing.

For some, it's not.

It's hard.

The companies are still struggling

with finding the right balance with working from home and working

in the office.

-There is, of course, a culture in some organizations

whereby the quality of your work

and the quality of your dedication to the organization

is measured in the amount of hours you're prepared to work and the amount

of personal commitments you're prepared to give up for your employer.

Nina, you're a labor inspector, is this something you've come across?

-Yes, definitely.

Also, you come across what we can call shadow work,

where you actually have workers staying longer,

working in their breaks.

Not saying that they do the extra work because they don't want the managers

to tell them not to, because this is the meaning of their work

to do this.

This usually occurs in sectors where you work with people like patients

or students or citizens where you just feel

that you spend too much time on bureaucratic procedures, registration,

or just have too much to do.

You can't give the care to the patients if you're a nurse that you feel

that you have to do.

Your work just loses its meaning.

I think that's one thing to add to the list.

I agree with the list ILO and WHO has made,

but I think the meaning of work is also really,

really important.

The fact that when you leave your workplace,

you feel that you've done something that actually makes a difference.

That makes people ill when they're not capable of doing that.

On top of that, if you have a manager that pressures you,

or you have co-workers, you don't have time to speak to,

or nobody seems to understand, you don't get any autonomy or control

of your work, then you have the cocktail.

That really makes people ill.

-Now, I can hear managers and employers saying,

"Well,

we can't regulate for stress and mental health.

Some employees are more prone to it.

Some are not.

It's not an issue for us."

What would you say to that, Nina?

-Well, I would say two things.

First of all, you say that people are different.

That's basically what they're saying.

They say that, of course, because we are different

and we have different personalities, we have different skills,

we have different mental health, then we can't regulate

because it's basically an individual problem.

To that, I would say look at, for example, when how we regulate chemical substances.

Here, we say that if 1 in 1,000,

just to give an example, can develop cancer for being exposed

to dangerous substance for 40 years and 8 hours a day,

that's quite a lot, then that is too much time.

We need to regulate and we need to lower that limit value.

Of course, you also have different genetical mixup.

Some people get cancer, some don't.

That is also an individual difference.

It's not your fault.

When it's an individual difference in your psychosocial

or your mental makeup, then we say it's your own fault.

I think that's basically a problem.

That is what is changing now.

I'm really happy about that, that you're trying to change the concept

and saying it's about the environment.

It's about what you are exposed to, the hazards you're exposed to

in the psychosocial working environment, and those you can regulate about.

That was my first point.

The second point is we have countries that done it.

We did it in Denmark in 2020.

They did it in Sweden 10 years ago.

Belgium's done it.

There are other countries all over the world that's done it.

What you do here is that you pinpoint those risk factors

that Susanna mentioned before also.

You pinpoint them in the regulation.

You say that your workload has to be manageable within the time,

so you can't put more workload or more tasks on people

than they have time to do, for example.

It's not a limit value.

You can't do that, but it's pinpointing

what is that you have to do as an employer.

You have to make sure that this is safe and healthy.

That also gives the labor inspector the means to go and inspect this.

I've done that myself, and you can do that.

You can make improvement notices saying,

“Well, this is just unhealthy because the workload is too high

or there is a mopping going on.

There is harassment going on.

There's violence or threats of violence.

It's unclear objectives.

It's unclear job demand.”

You can make improvement notice

or you can even find employers for not actually dealing with that.

It's definitely possible.

It's a little bit different from what we do when you look

at the physical occupational health and safety, but you can do it,

and thereby, you can avoid saying it's

the individual's fault, basically.

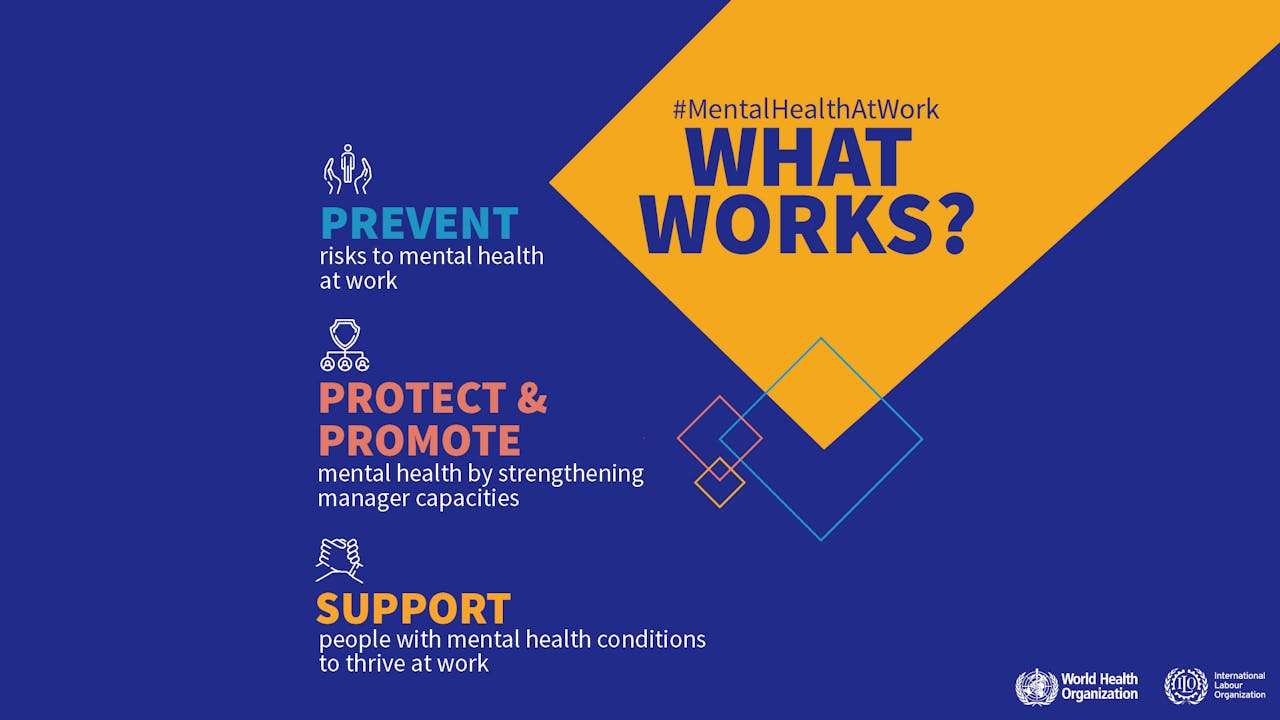

-It's important that organizations build an enabling environment.

There are basic three steps that companies can do or organizations.

It applies to both.

First of all, they need to prevent harm.

It's employer's duty to prevent harm, just as Nina said.

There are these lists, there are checklists.

There are wonderful resources for companies to go after.

Then the second step is to protect and to promote.

The protection and promotion is the strengthening of awareness

of mental health issues of stress

and also training of especially managers.

Because there's a huge, this is the biggest gap perhaps

in organizations at the moment that the managers don't know what to do

and they've been thrown into the role of mental health providers,

counselors.

It's absolutely not in their skillset.

-Yes, it's easy to dump everything on managers

and say it's poor management, but maybe they need to be given the tools

to do this.

-They do, and if you look at business schools

and training, for example, there's absolutely nothing

around these topics.

Now, it's coming slowly in some of the leading business schools,

but I work in this space as well, and it's quite shocking actually

how little it's being done in this area.

The line blind cannot lead the blind.

To go to back to that model, the three-step model,

one, prevent, two, protect and promote, and three,

support.

Support those who are unwell, who have actually mental ill health

rather than mental health.

With that package, you create an enabling environment.

I have seen this in practice when organizations embrace this model,

it does make a difference.

It doesn't happen overnight,

but the culture will change.

-It is a cultural change as well as specific measures.

-It is cultural change, yes.

-Is that one of the signs of a healthy employment organization,

would you say?

A culture that respects and values and looks out for mental health?

-Yes, absolutely, and younger generation

really does want to work for organizations that are healthy.

-I totally agree with the training of managers.

I think just to give you some idea of also what we are talking about,

we have been doing this in the Danish Trade Unions

with two collective agreements, and we have completely oversigned.

What you say, that's just too many managers who wants

to join these courses than we have seats, basically.

It's so popular because the managers themselves

are saying, “We want to deal with this,

but we just don't know how, because it's not that easy.

Give us some help.” I think also as trade unions and their social partners,

we should also do this together and to make sure that there is

a possibility for managers to get this training because it matters

what the training is about also.

In my perspective, it's really important to train

the managers in the psychosocial risks and how to organize work in a healthy way.

You shouldn't expect them, like you say, Susanna,

to be like mental health counselors or doing therapy with their workers.

No. Their job is to organize work and to make a good environment

where people collaborate and support each other.

I think that's the focus for the management training.

-I think that managers, at the moment, are the most stressed group in workplaces.

I've seen some statistics where 96% of managers or leaders feel burned out.

Over 70 have experienced depression.

Over 60 no longer want to lead.

These are shocking statistics, and my experience is the same as Nina’s

when I work with managers or I train them.

There's a certain level of desperation saying,

we have to be everything for everybody and who's taking care of us.

-They are passing down the stress to the lower-level employees is

what you mean that, actually, this is a message that has to come right

from the top, what is often called the C-suite

or senior management? -Yes.

This change does have to happen at that level because, otherwise,

you throw this at managers, and especially HR is caught

between the rock and the hard place these days.

They don't have the means, they don't have the budgets,

and they're expected to do, one, miracles basically with nothing

or very little, let's put it that way.

I'm advocating, absolutely, it's very, very important

that C-suite embraces this and sends a clear message.

In those organizations that I have worked with,

where the C-suite is behind it,

the culture is different and the managers are also,

even though it may not be perfect, because there's no perfect organization,

it's still much better.

-Right. Let me put to you both a final question.

What I'd like to know is whether you think we really are at a moment of change.

On the one hand, COVID-19 has brought to the fore issues

of mental health and workplace.

On the other hand, we are going into what looked

like very dire economic times when companies and employers are going

to be watching every penny.

Are we really at a moment of change for mental health in the workplace,

or is this a full storm?

Susanna, let me start with you.

-I think now we are at the threshold at an Industrial Revolution 2.0.

We can no longer ignore this.

The stressors that we have around in the current world,

we cannot ignore them.

Mental health has to be improved if we are to survive as an organization.

-Nina, what do you think?

-Yes, I agree, and I think what we have to do now is

we have to look more about the work we are doing and the priorities we have

in the workplaces.

Because are we doing the right tasks, basically?

Are we doing too much? Are we doing the wrong things?

It's because if we have to save money on one hand

and also protect the workers' mental health,

that is completely necessary.

We may look

into a few years where things will not get better,

not just at these next few years, but I think after that,

I think we are going to see a change because after COVID-19

and after this crisis, I think we've learned so much.

Like Susanna says, we cannot ignore it, so we will start working

on it and maybe finally start to realize that the psyche

has also limitations.

It's like we say, "Oh, we can just put a little bit more on top,

a little bit more on top.

You can do a little bit more, you can do a little bit faster."

We know that the body can't do that.

Why is that we keep thinking that we can do that when we look

at people's mental health?

-That's a great note to finish on.

Nina Nielsen and Susanna Harkonen, thank you so much for your time

and your contribution because that's all we have time for in this show.

Thank you too to you, our audience, and I hope you will join us again soon

for another ILO: Future of Work podcast.

For now, goodbye.

[music].

Find out more

WHO and ILO call for new measures to tackle mental health issues at work

Press Release

Guidelines on mental health at work

ILO/WHO Joint Policy Brief

Mental health at work

WHO Factsheet

Safety and health at work

ILO Topic Portal

Inner Work

Website

Danish Confederation of Professional Associations (Akademikerne)

Website