My brother and I started working during the tobacco harvests when I was seven and he was eight. There wasn’t really an alternative. My father was a tobacco worker and his earnings weren’t enough to cover the costs of our school supplies and clothes. It was the only way to make ends meet.

We would work during the summer months of December, January, February and March. We worked in the fields, loading and unloading the driers and helping wherever we were needed. We would see other children playing while we had to carry on with our work.

My brother and I knew that it was our way of contributing to the family’s income, and to our education. We also knew that almost inevitably our future was to continue working in the fields. So, we worked to be able to go to school and to earn our own money.

My brother and I around the time when we started to work in the tobacco fields. Here we are with our family for our first communion.

© Daniel BerruezoWe bought school supplies and clothes for the whole school year with the money we earned. It meant that work was almost obligatory for us. Otherwise we wouldn’t have had what we needed for school.

Although this experience marked my life in a negative way, we never felt resentment nor anger towards our parents. But we do feel that we missed out on play and sharing with other children. We couldn’t live the lives of normal boys.

My brother and I missed out on play and sharing with other children. We couldn’t live the lives of normal boys.

We continued as tobacco workers until we were 22 and 23 years old. Eventually we took over the farm and had our own production enterprise.

My childhood experiences working in the tobacco fields mean I understand how other child labourers feel, and what pushes their families to put their children to work.

I know what it is to work in the tobacco fields. This is me as a teenager lifting a bundle of tobacco leaves onto the back of a truck.

© Daniel BerruezoIn 2008, I started working at the Ministry of Labour in the province of Salta. The Minister at the time realised that a team from the ministry needed to work in the Lerma Valley so they could monitor not only undeclared work but also child labour. The Lerma Valley is the largest area of tobacco production in the province.

I head up that team. With my experience I met all the conditions necessary for the role. I had been a child labourer. I had been a tobacco employee, and I had been a tobacco producer. I knew the work that was involved and the activities where children would be working.

My childhood experiences working in the tobacco fields mean I understand how other child labourers feel, and what pushes their families to put their children to work.

A large part of what we do is to constantly raise awareness about child labour and tell communities that children should not work, that they should not do anything other than be allowed to develop as children.

The challenge we face is that in society in general, people think it is normal and right for children to work. So that is what needs to be changed, especially among those who have the power to make decisions. They need to understand that child labour is not the best thing for children.

We have developed ways to prevent the occurrence of a lot of child labour through the children’s centres that operate during the tobacco harvest. These have been set up by the Tobacco Industry Chamber in collaboration with the government of the province of Salta and other institutions. With their children taken care of, parents can work without having to worry about them. It seems to me that this is one of the best and most successful policies helping to prevent child labour in this area.

Also, with modernisation, different types of driers are being used. Because of their design, children cannot work with them easily. This changing reality has also meant that fewer children are working.

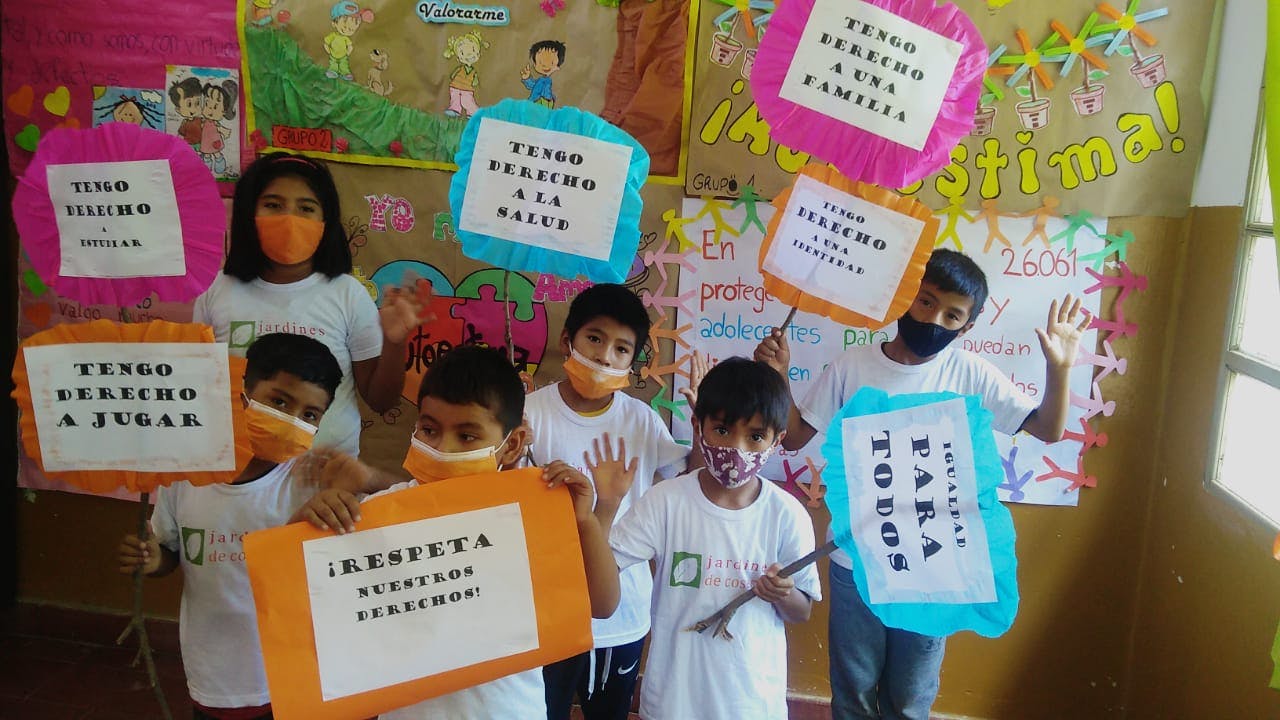

Children at one of the centres set up during the tobacco harvests. They hold up signs they have made with phrases such as “I have the right to play” and “Respect our rights!”.

© Cámara de la Industria Tabacalera, ArgentinaI found out about the ILO Offside project through my work. They invited us to participate in a training course on the prevention of child labour.

On the course we learned about other sectors where children are working. Elsewhere in the province of Salta, children are working in the wood industry. In my area they work in tobacco and in other areas child labour occurs in vegetable growing. Children can be found working everywhere, even in commerce.

Doing courses like this helps me in my work. I learned a lot of things that I didn't know about or didn't have a clear idea about before. I learned about how to detect child labour, how to implement policies to reduce child labour, as well as how to protect adolescents who are working. In our tobacco-growing area, a lot of adolescents are working without the necessary protections.

I don’t want my son to miss out on childhood experiences, like I did. I want him to simply enjoy his childhood and for him to fulfil all his dreams when he grows up.

© ILO/OIT Gastón ChedufauMy dream is that child labour will be eliminated. I think it’s the dream of many people - not only that children stop working but that they and their families receive support from the state and from intermediate institutions so that children don't need to work. I think children end up working because of a palpable need.

A lot of progress has been made. Although I am very happy about this, we need to continue to do more. I always say this whenever this issue is discussed. During the ILO course, for example, I said that we need to have more sports facilities, including at the children’s centres during the tobacco harvests. This would help to attract more children and would stop them from working.

My dream is that child labour will be eliminated. There were so many footballs that I didn’t get to kick and many other experiences that I missed out on as a child.

I am now married with two children. As a father, you always try to give your child what you didn't have, don't you?

There were so many footballs that I didn’t get to kick and many other experiences that I missed out on as a child. I want my children to enjoy their childhood as much as possible and to fulfil their dreams.

Children should be able to take advantage of education, sports, art, and music - all the things that will surely awaken the potential in every one of them and give them the capacity to develop fully into adults.